16.04.2019 - Studies

The stocks of sovereign debt held by banks especially in countries with vulnerable public finances and weaker banking systems have increased of late.

The stocks of government debt in the bank balance sheets of the southern European member states of the euro zone, which are also those with weak public finances, rose significantly from 1.2% to almost 14% in Portugal, from 5.4% to 12.1% in Italy and from 3.1% to 9.4% in Spain. Either could a further deterioration of public finances cause a banking crisis or growing problems in the banking sector could lead to a sovereign debt crisis.

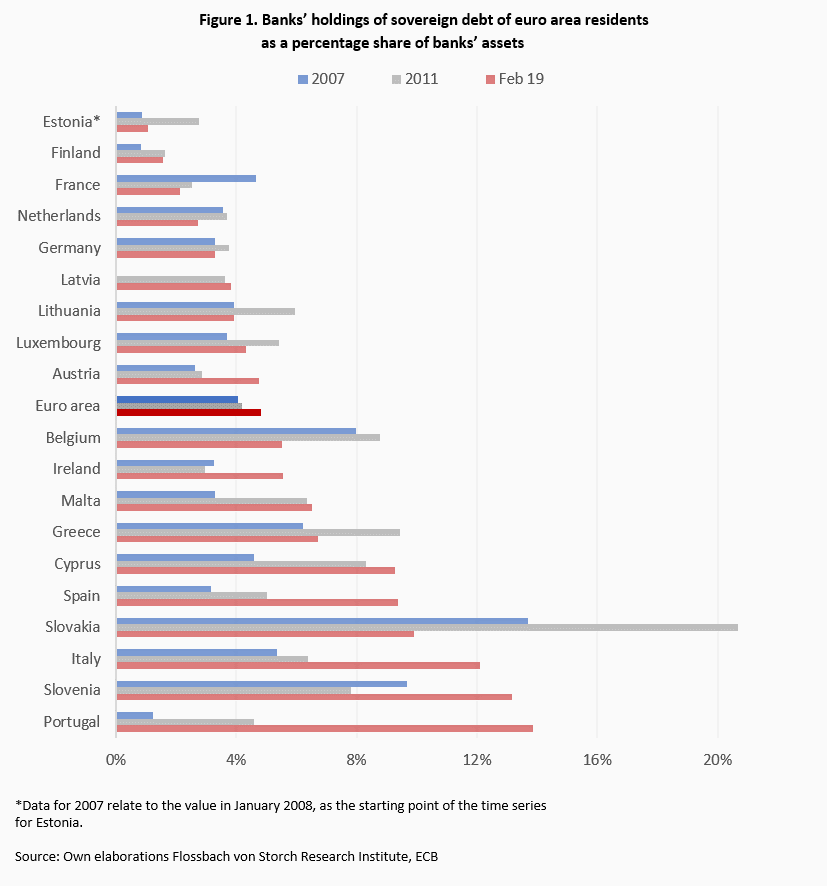

Banks’ holdings of sovereign debt rose only marginally in the euro area average from 4.1% of the balance sheet total at the end of 2007 to 4.8% in February 2019. But the holdings of banks in southern euro area member countries with weak public finances rose significantly over the same period, from 1.2% to almost 14% in Portugal, from 5.4% to 12.1% in Italy and from 3.1% to 9.4% in Spain (Figure 1).

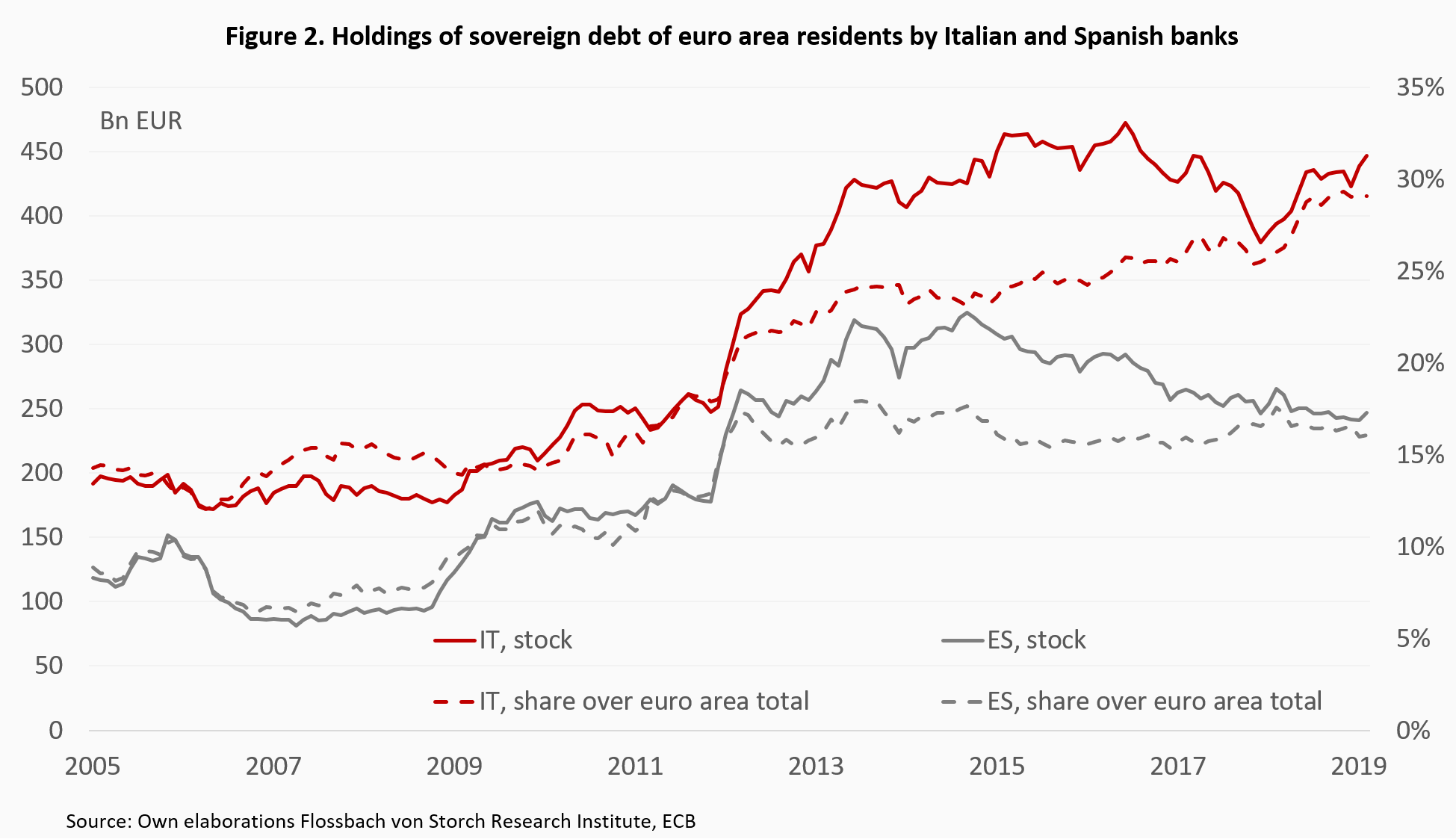

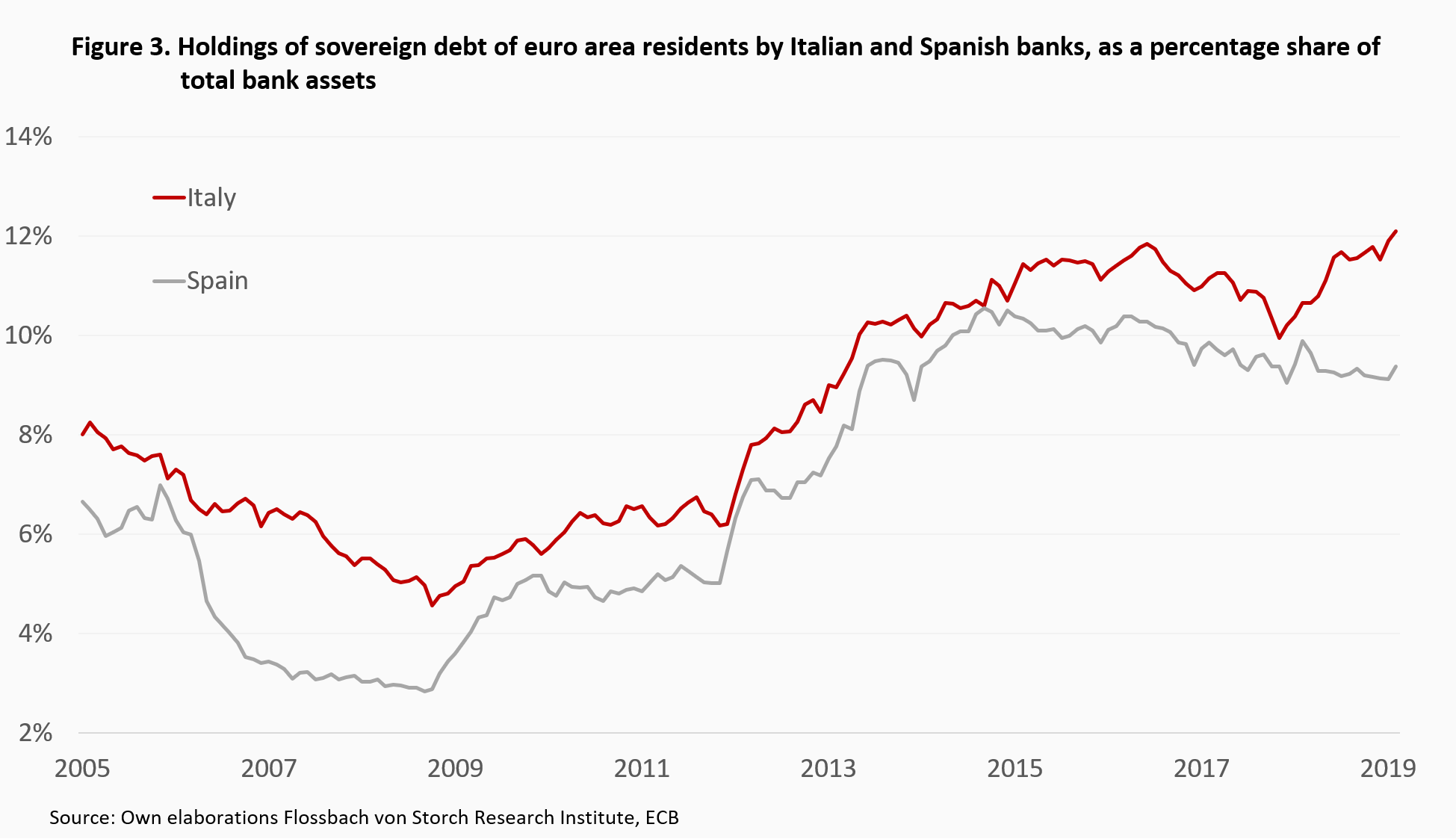

To assess the systemic dimension of increased government bond holdings, we analyse developments in more detail in Italy and Spain, two large euro area countries with high sovereign bond holdings by domestic banks. Both countries experienced a pronounced rise of banks’ sovereign bond holdings in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis, both in absolute terms and relative to the euro area aggregate as well as relative to the size of the banks’ balance sheets (Figures 2 and 3).

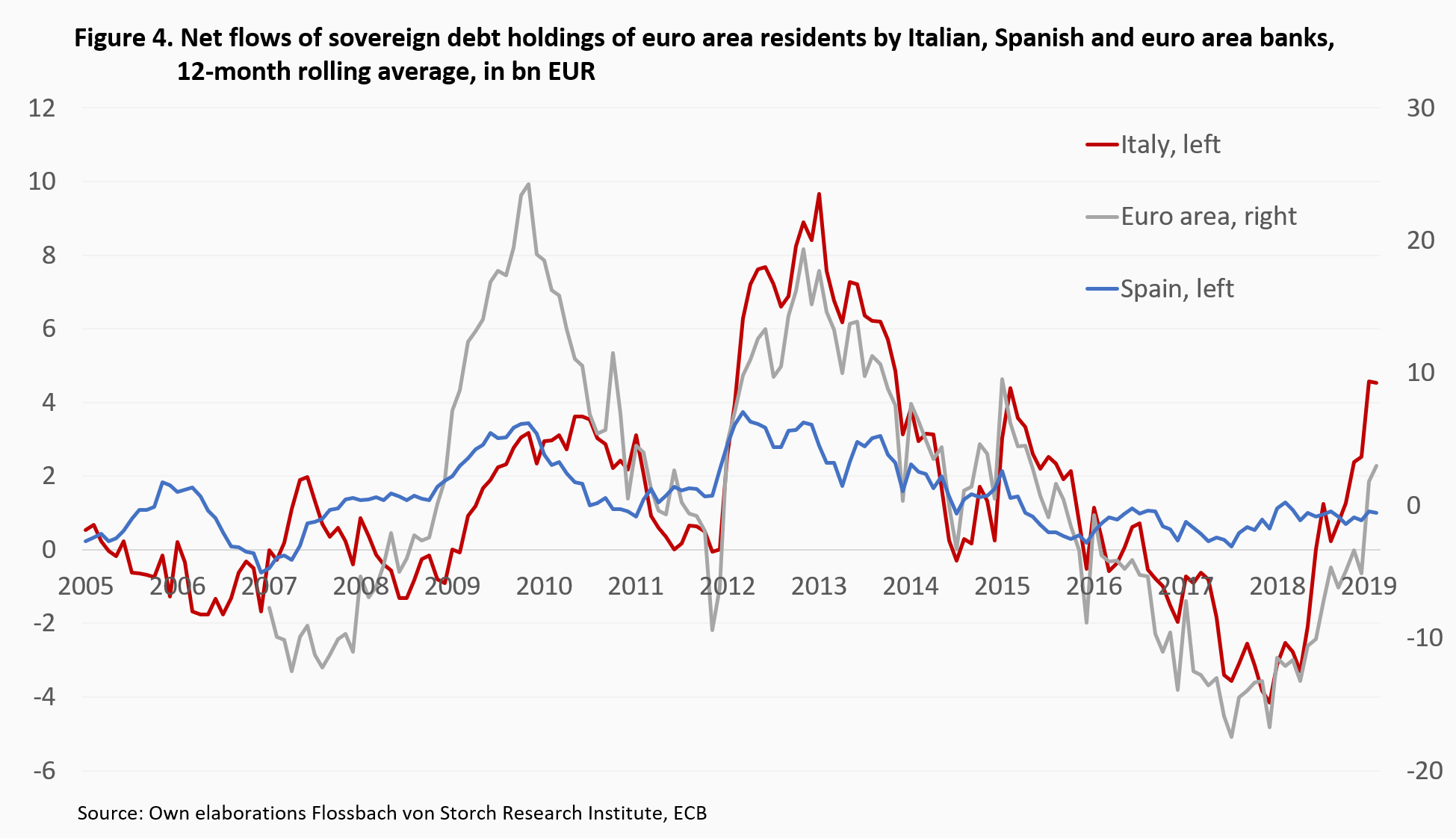

It is worth noting that net flows of sovereign holdings within the euro area were to a large extent driven by the activity of Italian banks and less so by Spanish banks (Figure 4). Moreover, Italian banks have stockpiled their holdings mainly during turbulent times of the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area and during the sovereign bond market stress associated with the Italian elections in early 2018. Spanish banks were also active in search for yields in the context of the European debt crisis, but not to the extent seen in Italy.

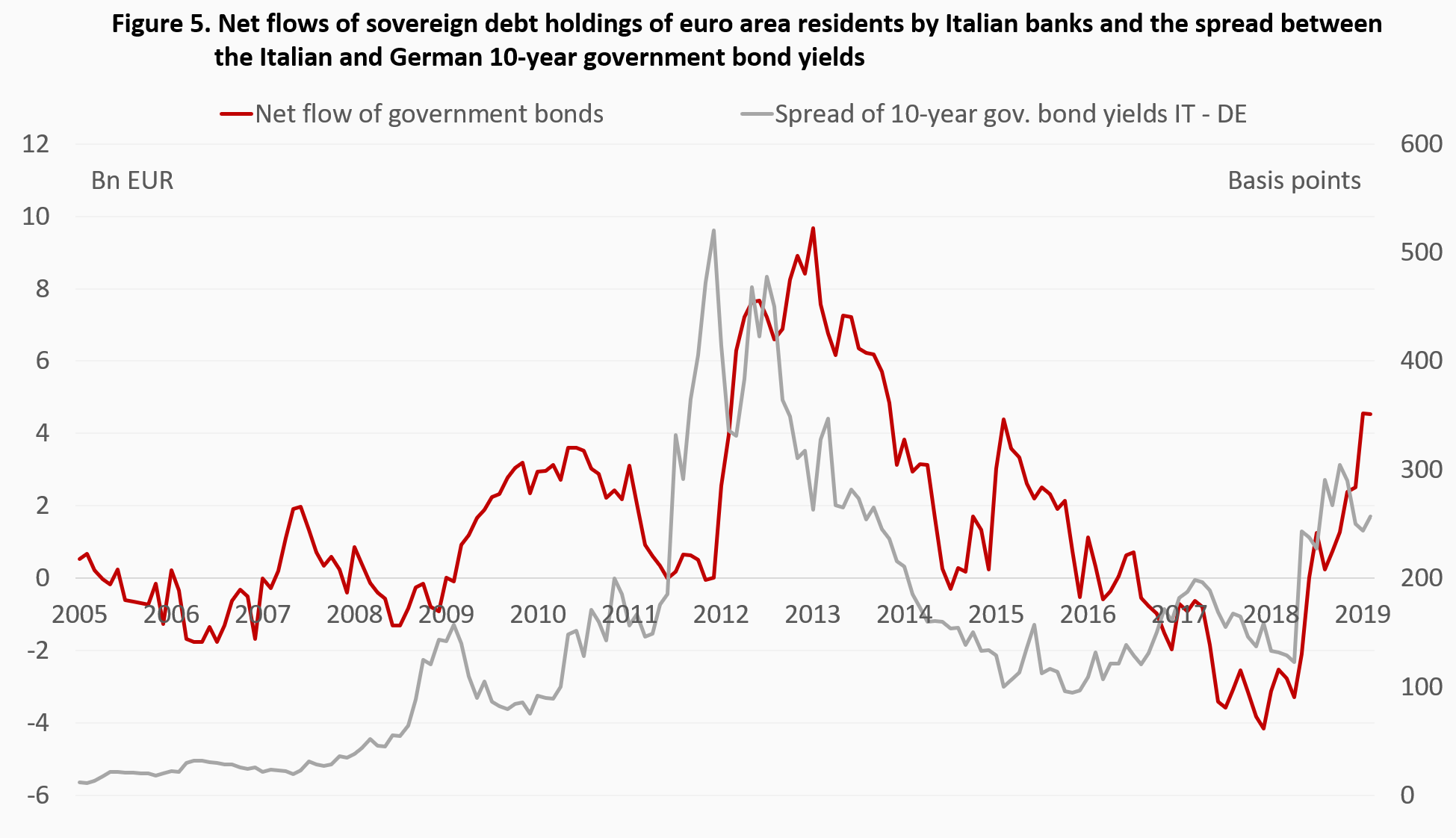

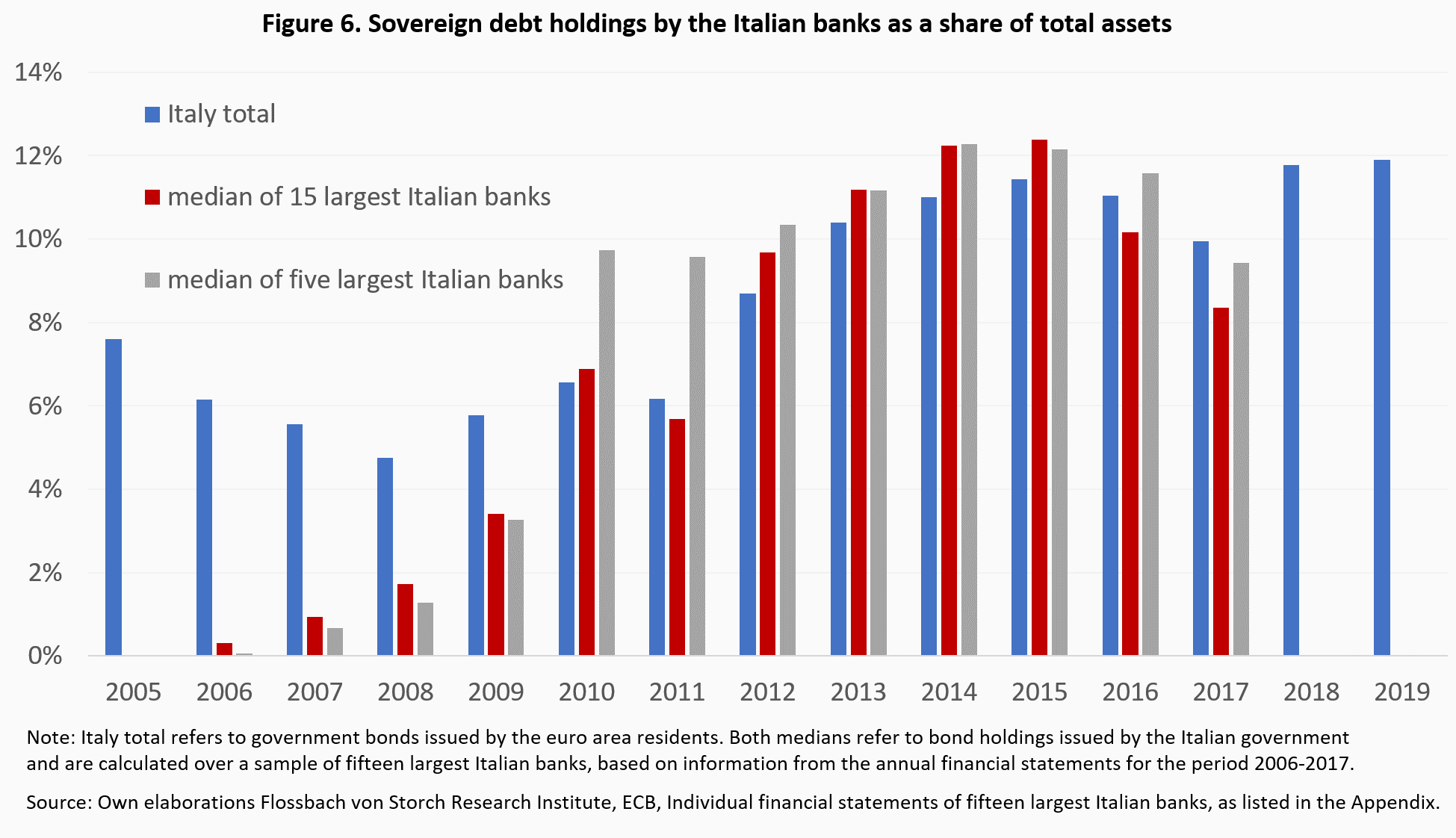

There is no doubt that bond purchases by Italian banks have eased funding difficulties of the Italian government. First, since the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12, government bond purchases by Italian banks have closely followed the spread between Italian and German 10-year government bond yields (Figure 5). Second, changes in sovereign bond holdings of all Italian banks were closely aligned with changes of Italian government bond holdings by the fifteen and five largest Italian banks (Figure 6). From this we can conclude that changes in overall government bond holdings by all Italian banks were strongly influenced by changes in their holdings of Italian government bonds, and that the largest banks have been most active in engineering these changes so far.

Apart from banks, also insurance companies could suffer the negative consequences of the broader sovereign-financial sector doom loop, as – due to regulatory requirements – they hold substantial amounts of government and bank bonds. In the assessment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), European and particularly Italian insurers are more exposed to the impact of rising sovereign and corporate bond yields than the banks.1

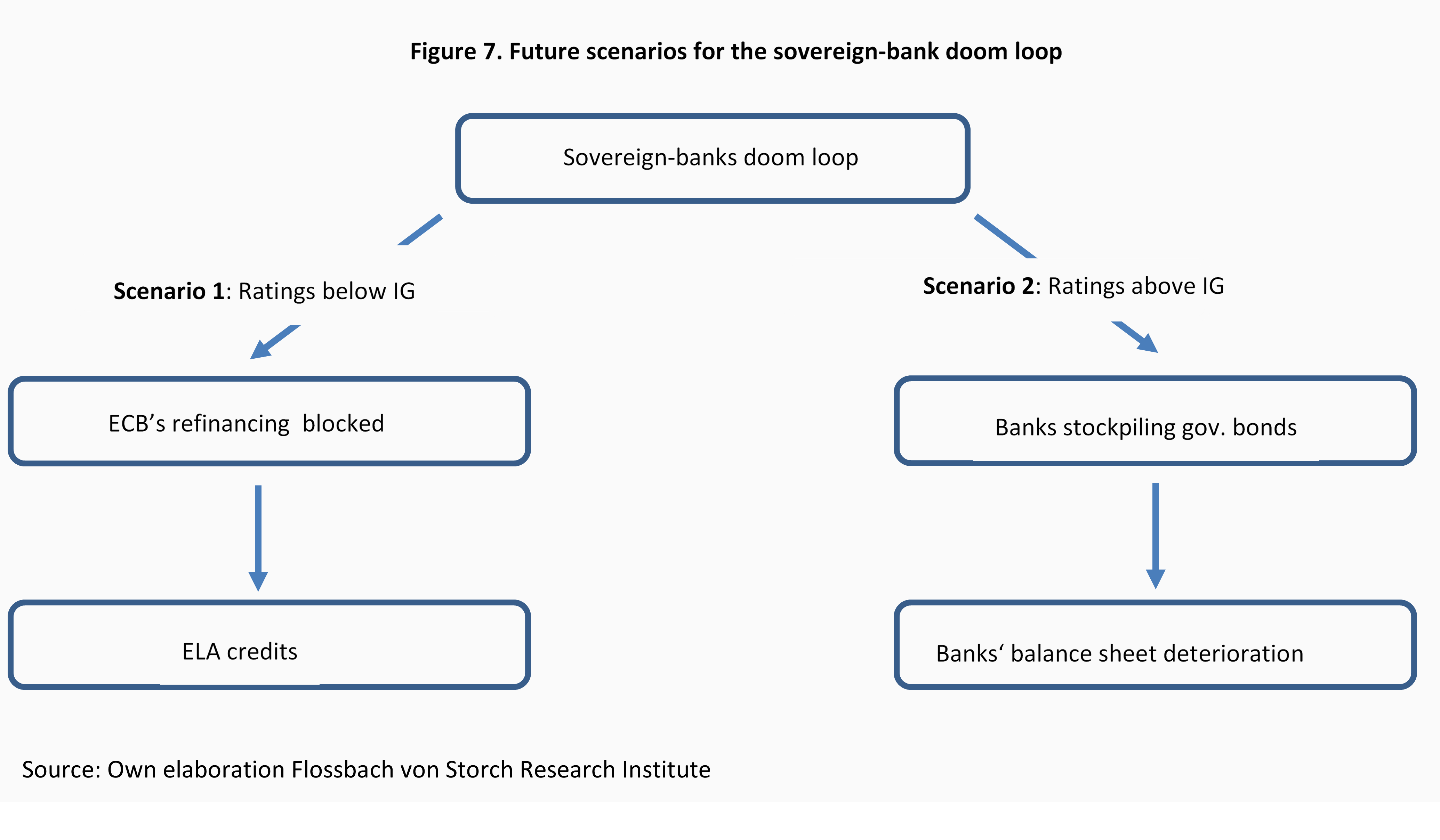

Weakening Italian public finances and strong reliance on Italian banks for public funding make Italy most vulnerable within the euro area for the sovereign-bank doom loop. Looking ahead, two possible scenarios seem plausible (Figure 7).

Scenario 1: A further deterioration of public finances leaves limited space for the rating agencies to keep Italy’s rating at investment grade level. Should the ratings of all four major rating agencies (Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, Fitch and DBRS) fall below investment grade (IG), banks won’t be able to use such bonds as collateral in the ECB’s refinancing operations. However, experience teaches us that this scenario is not very likely. As the case of Portugal in September 2016 demonstrated, there is always at least one loyal rating agency, be it the smallest, which delivers politically desired ratings. Should, nevertheless, all four rating agencies rate Italy below IG, the Italian banks would be excluded from the ECB’s ordinary financing through usual monetary policy operations. In this case, however, so-called ELA (emergency liquidity assistance) could be granted to solvent financial institutions “facing [temporary] liquidity problems”.1 Such credits were extended in Greece in 2015. Responsibility for the solvency and liquidity assessment lies with the country’s prudential supervisor. The ELA instrument can be used for 12 months, but the period can be extended “following a non-objection by the [ECB] Governing Council requested by the Governor of the NCB [national central bank] concerned”.2 This instrument could therefore keep the banking system afloat for an extended period, but it would not eliminate the possible distress of sovereign funding, with further mark-to-market losses on banks’

holdings of government bonds.3 Insurance companies with large holdings of government bonds would be negatively hit as well. In this case, equity cushions of both groups of financial institutions could fall below critical levels. Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) by the ECB could stabilize the government bond market and ease the pressure on banks and insurances. But an adjustment program with the ESM would need to be concluded for OMT can be implemented.4

Scenario 2: If at least one of the four rating agencies maintains an IG rating for Italy, it is likely that banks will continue buying bonds of the Italian government, as they have done so far, despite – or perhaps because of – rising yields. But the risk that government bond prices slide further implies that the banks’ equity capital would suffer losses and thus the banks’ balance sheets would deteriorate. This is likely to raise bank funding costs, which would be passed on to companies and households in terms of higher interest rates on loans. Not only banks, but also insurance companies with high government bond holdings would be hit by mark-to-market loses. All this, in turn, would put further pressure on the government’s refinancing capacity.

To encourage domestic investors, the Italian government presented plans to introduce tax breaks for the purchases of government bonds held on individual savings accounts to maturity (Cir, conti individuali di risparmio). But it is very unlikely that an analogous strategy would be extended to banks. The Italian government currently has only limited leeway to force banks to buy government bonds because of regulatory liquidity requirements under the net stable funding ratio.5

Policy makers are aware of the risks associated with the sovereign-bank doom loop.7 But instead of reducing risks and relying on capital market funding of governments they look for public alternatives to private bank financing at the euro area level. It has been suggested, for instance, that the European Stability Mechanism (EMS), which is designed to provide financial assistance to states and banks with strict conditionality, be transformed into a European Monetary Fund (EMF) providing more generous funding for governments shut out of capital markets. Moreover, to cut the sovereign-bank doom loop at the national level, efforts have been strengthened to introduce a common deposit insurance scheme (EDIS). Both proposals are aimed at transferring risks from individual countries to the community of euro area member countries.8

Risk sharing at the euro area level reduces the incentive for risk reduction in countries where the risk is created. Hence, instead of reducing risks through risk pooling, the proposed schemes are more likely to increase risks and transfer them to financially stronger countries. This is well understood by the latter, but opposed openly only by the smaller countries within this group, such as the Netherlands. Governments in the larger countries, among which Germany, tend to pay lip service to political correctness in EU policy matters.

Based on the size of individual bank’s total assets above €10 billion as of December, 31 2017, we analysed balance sheets of 15 Italian banks: 1)Unicredit, 2)Intesa Sanpaolo, 3)Banco Popolare di Milano, 4)UBI Banca, 5)Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, 6)BPER Banca, 7)Crédit Agricole Italia, 8)Credito Emiliano, 9)Banca Popolare di Sondrio, 10)Banca Carige, 11)Credito Valtellinense, 12)Deutsche Bank Italia, 13)Banca Popolare di Bari, 14)Banca Sella, 15)Unipol Banca. These are the largest Italian banks (parent companies or large subsidiaries of foreign banks, as is the case for Credit Agricole, Deutsche Bank and Banca Nazionale del Lavoro) with the main business consisting in the loans provision. Consequently, we had to exclude some large banks (ICCREA and Cassa Depositi e Prestiti) having another business focus. Finally, we excluded Banca Mediolanum due to a substantial change in accounting standards, which occurred starting in 2014. The list of banks was constructed based on the report “Le principali banche italiane” by Mediobanca and on Bloomberg data.

We did not consider the two Veneto banks (Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca), since they become insolvent in summer 2017 and are no longer existent. We also excluded another problematic bank, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, which has been struggling for some time to avoid insolvency and was finally overtaken by Banco Popolare di Milano at the end of 2016.

1 See Chapter 1 “Vulnerabilities in a maturing credit cycle” in the Global Financial Stability Report of the IMF, April 2019. The full text is available at: www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019.

2 “Agreement on emergency liquidity assistance”, June 2017, full text available at: www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/Agreement_on_emergency_liquidity_assistance_20170517.en.pdf.

3 Ibid, § 6.1.

4 Such losses could be to some extent diminished by moving government bond holdings from mark-to-market accounts to held-to-maturity portfolios. As reported by the IMF in its Financial Stability Report (see footnote 1 for the reference), this tendency is currently observed for some banks. However, these adjustments would only diminish losses, rather than eliminate them. Moreover, by switching to held-to-maturity accounts the balance sheet flexibility is lost, as according to IAS 39.51 once the securities are moved in this direction, the move cannot be reversed.

5 See “Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions”, ECB Press Release, September 6, 2012, available at: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2012/Html /pr120906_1.en.html.

6 For more details, see Agnieszka Gehringer (2019), “The paradox of the ECB long-term refinancing operations”, Flossbach von Storch Research Institute, Macroeconomics 06/03/2019

7 This is evident in the reports by the European Systemic Risk Board (2015), “Report on the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures”, by the German Council of Economic Experts in its Annual Report 2015, and by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017), “The regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures – discussion paper”.

8 See, for instance, Sapir, A. and Schoenmaker, D. (2017), “The time is right for a European Monetary Fund”, Bruegel Policy Brief No. 4.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.