19.07.2019 - Studies

This study was prepared by Rudolph Tinaye Matete.

Will financial assistance in the context of a “Marshall Plan with Africa” reduce migration flows from Africa to EU countries? Our analysis of migration flows from 53 African to 28 EU countries in the period from 1996 to 2017 suggests that the answer to this question is “no”.

In order to reduce the “root causes of migration” the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation in 2017 developed a “Marshall Plan with Africa”. The title of the project refers to an initiative of the US Government taken in 1948 to assist Europe financially in the reconstruction of its economy from the ruins of World War II. Between April 1948 and December 1952 a total of about USD 14 billion was given to European countries, with USD 1.4 billion going to Germany. The idea of the “Marshall Plan with Africa” today is to channel official and private money to the continent so as to improve living standards and reduce incentives for emigration. However, past experience with development aid has shown that capital flows to developing countries are not a sufficient condition for improving living standards. Hence, the expectation that financial assistance in the context of a “Marshall Plan with Africa” will reduce migration flows from Africa to EU countries is questionable. Against this background, the present paper attempts to identify key drivers for migration from Africa to the EU and investigates, whether more investment from the EU in African countries can contribute to a reduction of emigration.

Drivers of migration

The economic literature distinguished between “push” and “pull” factors driving migration.1 “Pull” factors include the gap in living standards between the country of origin and destination, the number of migrants already residing in the country of destination, common languages, common historical experience and commercial ties through trade. “Push” factors include economic instability in the form of high inflation and unemployment as well as low potential growth due to weak institutions. But there are also financial constraints to migration, such as low incomes or travel costs over long distances.

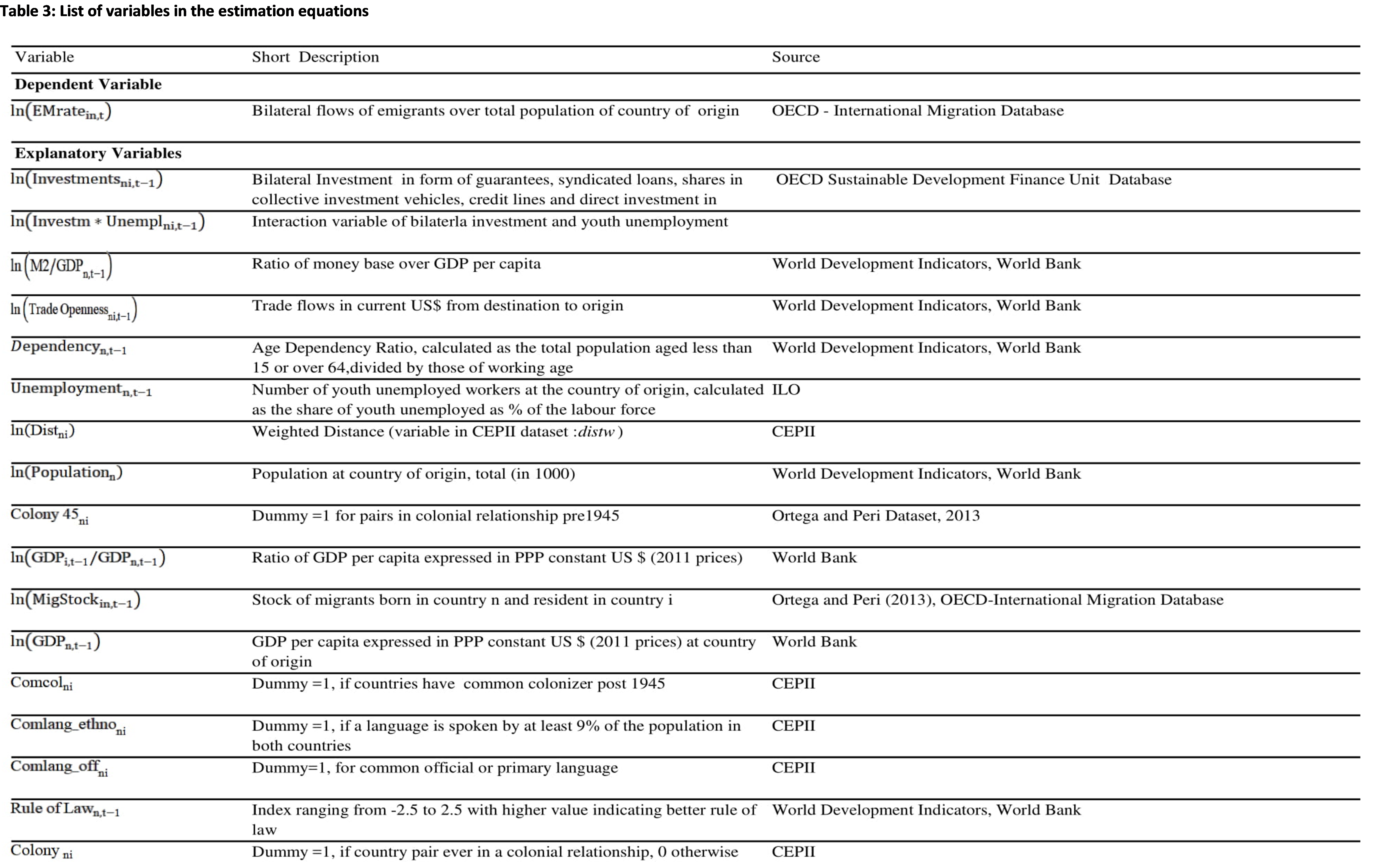

In the following we estimate a model explaining migration from African countries to the European Union with push and pull factors, migration costs and bilateral investment flows from EU countries to the African countries. Our sample includes the data from 53 African and 28 EU countries for the period from 1996 to 2017. We employ a Poisson Pseudo-Maximum-Likelihood (PPML) estimator for the pooled time series and cross country (panel) regression.2 To obtain elasticities between the dependent and independent variables we transformed variables into natural logarithms wherever possible. We also included country-specific dummy variables in our equation.

Empirical estimates

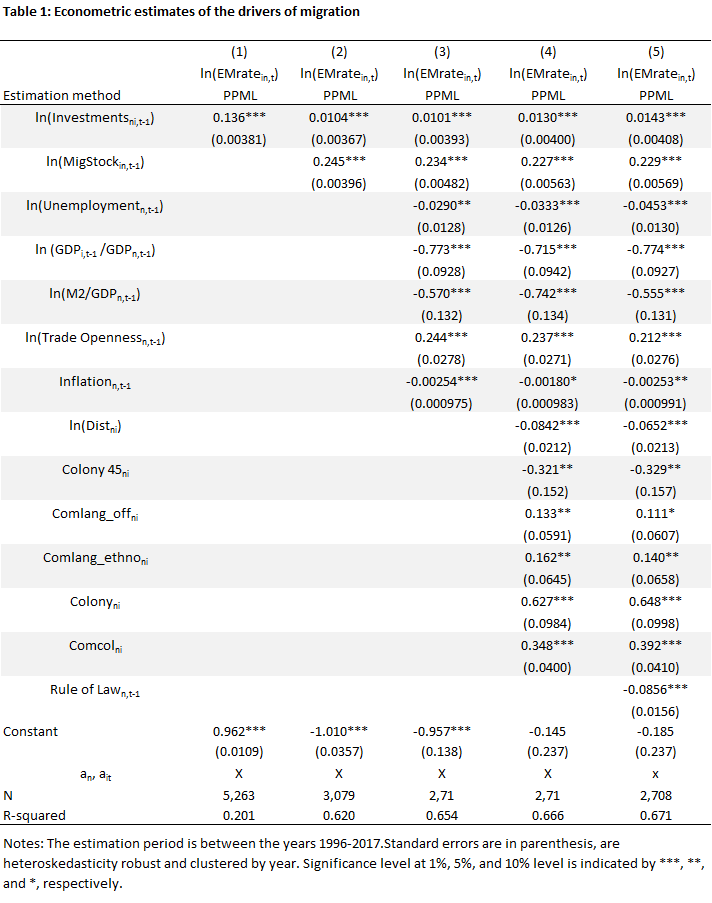

The results of our regressions are given in Table 1. We started by regressing bilateral migration flows on bilateral investment flows (column 1). The investment variable enters the equation with a positive sign and is statistically significant at the 1 percent level of error probability. This equation suggests that an increase in investment flows from EU country i to African country n raises emigration from African country n to EU country i. This is contrary to our expectations and the intention of the “Marshall Plan with Africa” to reduce migration by inducing more investment from EU countries in African countries. However, the regression equation has a low overall fit as measured by an R2 of only 0.2. Hence, we need to extend the equation by including other determinants of migration in order to check whether the result is robust.

For the first extension we included a “pull” variable in the form of the number of migrants from African country n already residing in EU country i. The result reported in column (2) of Table 1 suggests that this is an important factor explaining migration flows. A one percent increase in the number of migrants from country n already residing in country i raises the ratio of emigrants from n to i relative to the total population by 0.2 percent. The fit of the equation is now much better. The value of the coefficient for investment flows is still positive and statistically significant. But its value has dropped to close to zero, suggesting that a one percent increase in investment flows from country i to country n raises the migration rate from n to i by only 0.01% (which is an “economically insignificant” amount). It seems that the investment variable in the estimation equation reported in column (1) picked up pull effects created by the closeness of the relationship between emigration and immigration countries, which are better captured by the stock of migrants already residing in the destination country of emigrants.

In the next step we added more variables, which in the economic literature are expected to pick up push and pull factors. The unemployment rate of young people (aged 15 to 24 years) is often seen as a push factor for emigration. However, it enters the equation in column (3) with a negative coefficient, which is statistically significant. How can it be that an increase in the unemployment rate for your people reduces emigration (albeit by a small amount)? We suspect that this variable picks up the financial constraints to emigration. The higher the rate of unemployment of young people, the poorer is the country and the less able its residents are to afford the cost of travel to better places. The ratio of GDP per capita in the immigration country to GDP per capita in the emigration country is often regarded as a pull factor and hence its coefficient should enter the equation with a positive sign (meaning that the higher GDP per capita is in the immigration country the more attractive is it to go there). However, this variable enters equation (3) with a statistically significant coefficient with a high negative value. Thus, the variable could pick up the fact that higher per capita incomes in the African countries make journeys to Europa more affordable.

The ratio of money (cash, sight, savings and time deposits as included in the aggregate M2) to GDP is used as a proxy of financial development in the emigration country and expected to enter the equation with a negative sign. This is indeed the case. Moreover, the value of the coefficient is large, suggesting that a higher level of financial development has an economically significantly dampening effect on emigration. Intense trade between two countries could be an indication of close relationships, which could have a positive impact on migration flows. And indeed, trade flows enter the equation with the expected positive sign and are statistically and economically significant. On the other hand, inflation in the emigration country could be expected to indicate economic instability and hence raise emigration rates. However, this variable enters the equation with a statistically significant negative coefficient. Although the value of the coefficient is small (and hence the variable economically not significant), we interpret this variable to pick up financial constraints to emigration. High inflation is often associated with low real incomes, which reduce the possibility to emigrate.

In the estimation equation in column (4) we add a number of variables picking up the strength of past and present relations between emigration and immigration countries. Specifically, lnDistni is the logarithm of a variable measuring the geographical distance between the emigration and immigration country. It enters the equation with a negative sign, unsurprisingly indicating that distance is a barrier to migration. Colony 45ni is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 when the emigration country n was a colony of immigration country i before the year 1945. This variable enters equation (3) with a statistically significant negative coefficient, indicating that past colonial relationships deter migration between the two countries. Comlang_offni and Comlang_ethnoni are dummy variables taking the value of 1 when a common language is spoken officially or by at least 9 percent of the total population in the two countries. Both variables enter the equation with a statistically significant positive coefficient, suggesting that common languages like the stock of migrants already residing in the immigration country exert pull effects on emigrants. Colonyni and Comcolni are dummy variables taking the value 1 when country n was a colony of i post 1945 and whenever it was a colony of i. Both variables enter the equation with statistically significantly positive coefficients, reaffirming the importance of historical relationships between emigration and immigration countries. The negative coefficient of the dummy variable picking up only pre-1945 colonial relationships suggests that the effects of past closer relationships fade of time.

Finally we added a variable measuring the quality of institutions to the estimation equation. We chose an indicator measuring the strength of the rule of law provided by the World Bank. This indicator enters the equation in column (5) with a statistically significantly negative coefficient, suggesting that emigration is lower the better the rule of law is in a country. However, the value of the coefficient is fairly small, and although the index enters the equation not in logarithmic form its influence on the emigration rate is moderate (as the index can take values only between plus and minus 2.5).

In comparing equations in columns (1) to (5) we note that coefficients of variables change only little when we add more variables and that the fit gradually improves. Thus, the equation in column (5) is the most econometrically efficient estimation equation for explaining determinants of migration between country pairs n and i. Our take-aways from this equation are:

Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to answer the question of whether financial assistance in the context of a “Marshall Plan with Africa” will reduce migration flows from Africa to EU countries. Our analysis of migration flows from 53 African to 28 EU countries in the period from 1996 to 2017 suggests that the answer to this question is “no”. To the contrary, bilateral investment flows tend to raise migration flows on the margin as they add to the strength of the relationship between emigration and immigration countries, which is a key factor for migration flows. Consistent with the economic literature our results suggest that emigration is lower when emigration countries either are quite poor or when they are more advanced. By helping African countries to strengthen the rule of law and develop their financial sector, EU countries could make a better contribution to reducing the “root causes” of migration than by pumping money to Africa in a “Marshall Plan with Africa”.

* Research to this paper was undertaken at the Flossbach von Storch Research Institute. I am grateful to Thomas Mayer for helpful suggestions.

1 For a survey of the literature see Rudolph Matete, “Do private and public investments from European countries deter migration from African countries?” unpublished manuscript, 23 May 2019.

2 See Matete (2019) for a detailed description of the data and the estimation method.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.