28.09.2021 - Studies

We are living in a far less globalizing economy today. Since at least the Great Financial Crisis the pace of globalization has slowed down significantly or even reversed in some areas. Although the COVID-19 pandemic seems to some extent to have interrupted this development, chances for a new wave of globalization are meagre – with painful economic consequences.

Recent (de)globalization trends

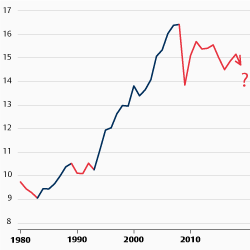

The most recent phase of globalization between the early 1990s and 2007 brought an unprecedented rise in economic, social, and political interconnectedness between nations worldwide. The KOF Globalisation Index, in Figure 1, increased from 43 in 1990 to 58 in 2007, with comparable and significant improvements in all three dimensions, economic, social and political. However, since 2007, marking the beginning of the Great Financial Crisis, the process has experienced a structural break. Especially the economic dimension of globalization has disappointed. This phenomenon is particularly reflected in a falling share of world merchandize trade over global GDP (Fig. 2).

There is some evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic alleviated some de-globalisation tendencies, since governments across developed and developing world seized a significant number of trade facilitating measures. Out of 402 trade measures (tariffs and non-tariff measures) introduced by governments worldwide between January 2020 and January 2021, 51% were deemed to facilitate trade (Fig. 3). Such measures involved, beyond tariff redemptions or exemptions, relaxation of authorization and licensing requirements as well as exemption from various forms of taxes on imported products.

However, most of these measures are only temporary – with some already terminated. Moreover, given the past crisis experience, especially of the Great Financial Crisis, the pandemic is likely to eventually spur another withdrawal from globalization, with governments seeking to protect national interests. Indeed, there is a recent trend – recognizable already before the pandemic – of governments increasingly referring to the need to regard public-health issues as a national-security imperative. This led to a remarkable raise of technical barriers to trade over the last years (Fig. 4).

More generally, the risk of overshoot in deglobalization is high, particularly if geopolitical tensions continue to fray economic relationships between the global superpowers. In the worse-case scenario, a chaotic retreat from globalization would likely induce vastly more serious problems.

Economic implications of de-globalization

A wide array of economic models undeniably shows that free trade and broader economic integration between nations bring net economic gains. Reversing these trends implies slower economic growth – everywhere. The most hit would be smaller developing countries, especially when being economically dependent on a narrow range of income sources, lacking a broad industrial basis or natural resources. But also highly diversified and technologically leading economies would suffer from shrinking real demand elsewhere.

There are further unpleasant economic consequences to expect. Just as globalization was a driving force of the past slow price dynamics and through this of low inflation and declining interest rates, switching the process on the reverse gear could eventually lead to widespread price and interest rate increases.1

Moreover, since deglobalization of trade often goes hand in hand with unwinding of financial ties, this could remarkably depress the borrower position of the USA – both in the private and public sector. Accordingly, attracting funds from abroad could become increasingly cumbersome. Furthermore, falling foreign demand for US debt could eventually undermine the US dollar’s role as a reserve currency.

Deglobalization could also mean a backlash in the global climate action, which is more desired today than ever before. Not only would the developed world turn to cultivate national interests, intensifying efforts to replace global sources of growth with domestic ones, at the expense of climate policy. More unstable trade relations with developing countries would likely mean weaker transfer of green technologies from developed to developing world. Finally, there is no reason to believe that the lack of willingness to cooperate on trade issues would be overcompensated with cooperation on the climate front.

There is no doubt that the current model of globalization needs adjusting, to more strongly account for the disadvantage of social and economic groups left behind the pace of economic integration. But dismantling the entire system, which for decades brought net benefit and improved wellbeing, is by no means an option. De-globalization is a negative-sum game, and if it goes too far it won’t spare any nation.

1 Tofall, N. F. (2019). De-Globalisierung und die neue Bipolarität. Flossbach von Storch Research Institute Wirtschaft & Politik 6/12/2019. Available at: , www.flossbachvonstorch-researchinstitute.com/de/studien/de-globalisierung-und-neue-bipolaritaet/.

22.09.2021 - Macroeconomics

by Thomas Mayer

06.12.2019 - Economics, Politics & Philosophy

Where does the strategic rivalry between China and the USA lead?