28.11.2019 - Studies

The ESG ratings of various providers sometimes differ significantly from one another. A responsible investor should therefore always form his own opinion.

With the rapid growth of the market for sustainable investments, the importance of corporate performance in the area of sustainability has greatly increased. As great as the agreement seems to be on the high relevance of the topic of sustainability, there is little agreement on the answer to the question of how the sustainability performance of a company can be measured at all. Various rating agencies offer assistance to interested stakeholders. There is no doubt that such ratings often provide valuable indications and food for thought. However, the lack of a common understanding of the term "sustainability" makes it unclear what such ESG ratings actually measure.

The present study shows that the assessments of individual ESG rating agencies sometimes differ significantly from one another. It is therefore appropriate to deal responsibly with the assessments and it's advisable to always get your own picture.

The trend towards "sustainable investment" has experienced a real boom in recent years. Rarely before has a topic on the financial markets unfolded a comparable dynamic in such a short period of time. At the latest since politics has discovered the topic for itself and has promoted it with the "Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth", it has become clear that the acronym "ESG" will probably also occupy the financial markets sustainably. This involves evaluating ecological (E) and social (S) aspects as well as the corporate governance (G) in the company analysis. But long before capital flows were actively channelled into "green" investments through regulatory intervention, the popularity of investments with a focus on sustainability rose sharply.

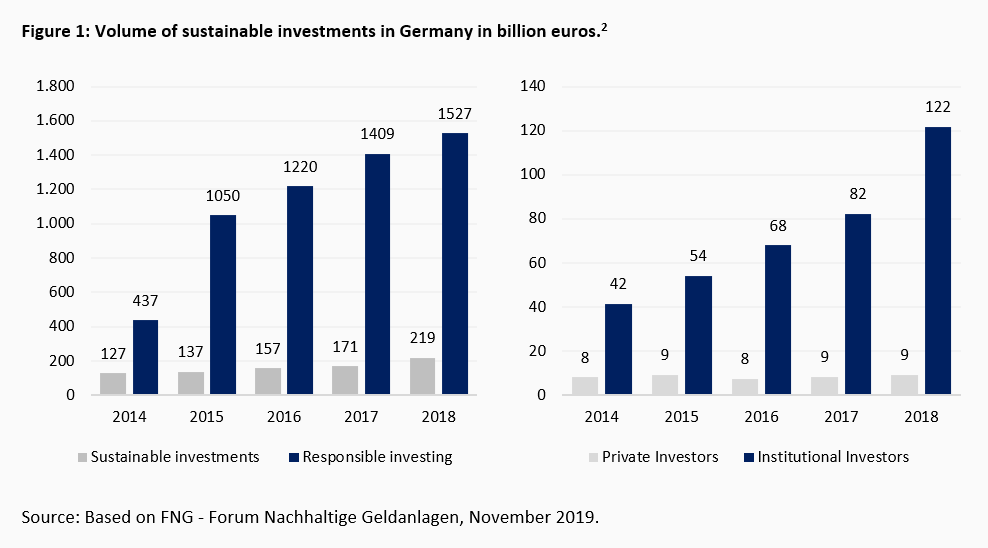

The Forum Nachhaltige Geldanlagen (FNG) puts the sum of explicitly "sustainable investments" in Germany at EUR 219 billion at the end of 2018 (see Figure 1, left)1. Compared with 2014, this corresponds to an increase of almost 100 billion euros or 73%. The increase in so-called "responsible investing" is even more pronounced. With this very broad definition, sustainability aspects are not implemented directly at the product level, but at the institutional level, for example through the commitment to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) of the respective asset manager. Based on this definition, the volume of money invested increased from 437 billion euros in 2014 to 1,527 billion euros at the end of 2018.

Against the background of the omnipresence of sustainability in the media, it is surprising that the high growth rates of explicitly sustainable investments are limited to institutional investors. Among private investors, the topic still has a niche existence (see Figure 1, right). The volume of sustainable investments by institutional investors in Germany tripled to 122 billion euros, compared with 42 billion euros in 2014. According to the FNG, church institutions and welfare organisations were the main drivers of this growth. At the end of last year, they accounted for 40% of invested funds, followed by insurance companies with 17%. In contrast, the volume of private investors at the end of last year was just 9 billion euros, after 8 billion euros in 2014.

With the strong growth of sustainable investments, the question of how sustainability and in particular the sustainability performance of a company can be assessed has gained enormous importance. While in a holistic valuation approach it should be taken for granted that risk factors resulting from non-compliance with minimum environmental and social standards or from aspects of corporate governance should be taken into account, it seems that the sensitivity for the consideration of such ESG criteria in the broad market has only been awakened in the recent past.

For a long time, the integration of ESG criteria in the evaluation process was hampered by the fact that there was hardly any reliable and at the same time value-relevant information that made a full ESG evaluation possible. Although the reporting obligations for non-financial performance indicators have been significantly extended since the implementation of the EU CSR Directive in 2017, companies continue to report on sustainability aspects often quite selectively3. All too often, the relevant reports are reminiscent of image brochures and hardly provide a suitable basis for an all-encompassing sustainability assessment. Investors' risk/return assessments often remain unaffected by the evaluation of the information provided. In addition, the information is not subject to review by the auditor.4 Standardisation of information, such as in financial reporting, is only possible to a limited extent with regard to ESG and is hardly conceivable in the same form, since such harmonisation would not be operationalisable to the same extent in practice. The significance of individual dimensions is very heterogeneous for specific industries, so that an overly strict standardization of information would not do justice to the complexity of the topic.

Since an annual report analysis therefore offers little prospect of added value and is also cost- and time-intensive, many market participants fall back on the assessments of external rating companies. In particular, fund companies that derive their products from global indices, such as providers of passive ESG funds, rely on this service. With the increased demand for ESG ratings, the range of corresponding ratings has increased significantly. Over the past decade, the ESG rating market has produced a large number of different ESG research providers, even though a concentration process has recently been observed.5 However, the market is still far away from oligopolistic structures, such as in the market for financial ratings. However, there are also a number of providers on the sustainability rating market whose ratings are receiving increasing attention. These include, for example, MSCI ESG Ratings or Sustainalytics. In addition, there are providers who examine equity funds with regard to various sustainability aspects, such as Morningstar or FNG.

The rating providers also draw on information from the annual and sustainability reports. However, these are supplemented by further information from publicly accessible sources, such as news sites or data from NGOs, as well as information resulting from direct dialogue with companies. Standardized questionnaires are frequently used for this purpose. As the study by Escrig-Olmedo et al. (2019) shows, the range of topics has expanded considerably in recent years, particularly with regard to ecological issues and aspects of corporate governance, while in the case of social issues a shift in focus rather than an expansion can be discerned.6

The central function of ratings is to reduce information asymmetries between the company and its stakeholders. In order to achieve this, the information provided must actually be useful for decision-making. This is assumed to be the case if they either reinforce or correct the addressee's assessment of the entity.

In the context of financial ratings, this means that users of these ratings arrive at robust estimates of whether companies will be able to meet their payment obligations on time in the future. This solvency can be understood as a function of the current debt situation and future financial strength. Various key figures have been established to measure debt and financial strength. These include, for example, the equity ratio or the ratio of interest-bearing debt to operating cash flow7. These ratios are causally related to creditworthiness. Financial ratings therefore have a clearly defined goal and an established form of operationalisation.

In the case of pure ESG ratings, the provision of information useful for decision-making is far more challenging. Neither the question of what a sustainability rating should measure nor the question of how this should actually be implemented can be answered in a universally valid way for potential users. In contrast to credit ratings, the target group is not limited to the comparatively homogeneous group of investors, but extends across all stakeholder groups due to the sharp rise in overall social awareness. But even within individual groups, the ideas about the actual added value of certain information are very different and dynamic. While one reader would like information onCO2 emissions in the case of the "Environmental" dimension, the other would like statements on strategies for minimising water use or on measures to protect biodiversity. The diversity of ideas about the concept of sustainability and the multidimensionality of the topic cast doubt on the usefulness of much sustainability information for decision-making by a large circle of addressees.

Irrespective of how the rating methodologies are presented in detail, corresponding evaluation models must meet the quality criteria known from empirical social research.8 These include:

ESG ratings are always to some extent subjective. Even if the ESG performance measurement is operationalised in the same way, there is still a dependency between the evaluator and the result achieved. This applies in particular to qualitative data obtained through interviews, as in this case the measurement result is influenced by both the analyst and the interviewee. A checklist-like valuation of given criteria increases objectivity, but this is usually done at the expense of validity (described below).

As the collection of ESG information often involves the use of interviews and questionnaires, as described above, which interview different people depending on the time of the survey, the assessment should produce different results depending on the time of the survey. Even if the same people are involved, the results are likely to vary as there may be unconscious distortions in the collection and interpretation of the data.

A rating is valid if the test contents are in line with the expected result. A sustainability rating should therefore measure how sustainably a company operates. This depends on the underlying definition of sustainability. There is no doubt that high ESG assessments should reflect low sustainability risks. Falsifications of this connection, however, are abundant. For example, Utz (2019) shows that ESG assessments offer no indication of scandals such as corruption, balance sheet manipulation, product recalls or environmental disasters. If a scandal becomes public, the corresponding valuations decline significantly in the aftermath.9 The example of the Volkswagen Group, which was confirmed as the industry leader in sustainability in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index with 91 out of 100 possible points seven days before the diesel scandal became known, is a popular example of the lack of validity of corresponding ratings.

In addition, although certain ESG ratings can be a valid measuring instrument for a certain group of addressees, this does not necessarily apply to other groups of addressees. The heterogeneity of the notions of the meaning of "sustainability" stands in the way of a standardisation of ESG ratings. A universally valid sustainability rating is therefore an oxymoron. It is not without reason that a uniform valuation standard has not yet prevailed in the market for ESG ratings, because it is not possible to value what cannot be defined.

In addition, the ratings, which are reduced to one point value, do not recognise the complexity of the issue and feign comparability between different ratings. However, this reduction in complexity is beneficial for many users, as it allows ESG topics to be conveniently integrated into the evaluation process or ESG indices to be created. It is difficult to assess the validity of a rating ex ante in individual cases, as the necessary transparency is lacking. However, if the rating companies were to disclose their methodology in detail, this would lead to competitive disadvantages.

The above considerations give rise to a certain scepticism as to whether ESG ratings can fully fulfil the function attributed to them. The following analysis shows that the doubts derived from the theory seem to be quite justified.

The evaluation compares the ESG scores of the providers MSCI ESG Ratings, Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM for the companies of the MSCI World Index. The respective ESG scores as of October 2019 are used for this purpose. Although the valuation logic is largely opaque for users, it results in comparable valuation results analogous to classic financial ratings. The aim of the evaluation is a cross comparison across all index constituents. There is no evaluation with regard to the validity of individual ratings.

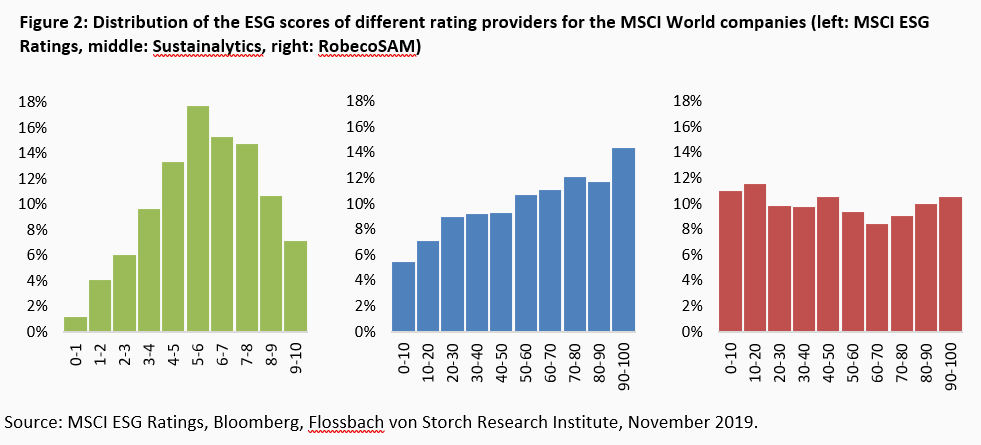

When looking at the rating distribution of the provider MSCI ESG (Figure 2, left), a normal distribution can be seen, although the left skewness is clearly visible, i.e. there are comparatively few observations in the range of low scores and comparatively many observations in the range of high scores. Only 11.4% of companies in the MSCI World Index score 3.0 or worse, while 32.6% score 7.0 or better. The average achieved value is 5.79. The rating results of the rating providers Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM range between 0 and 100 points. Sustainalytics (Figure 2, center) shows continuously increasing group sizes across the valuation classes. While 14.4% of the companies receive 90 points or more, only 5.4% of the companies end up in the lowest decenter. Exactly 40.0% of companies have a score below 50, while 60.0% of companies have a score above 50. Consequently, the average score of 56.8 is higher than the 50.0 that would have been expected if the distribution had been equal. This is surprising, since against the background of the evaluation logic (see Appendix) an equal distribution should actually result. RobecoSAM (Figure 2, right) shows approximately equally distributed point values across the classes formed, with a slightly increased density at the edges. The average score here is 48.4.

Figure 2 shows that the distributions of the scores vary considerably depending on the rating provider. This means that the providers of the analyzed companies in the MSCI World Index apparently arrive at different valuations. These deviations are often small, but in other cases the assessments are far apart, as the following examples illustrate:

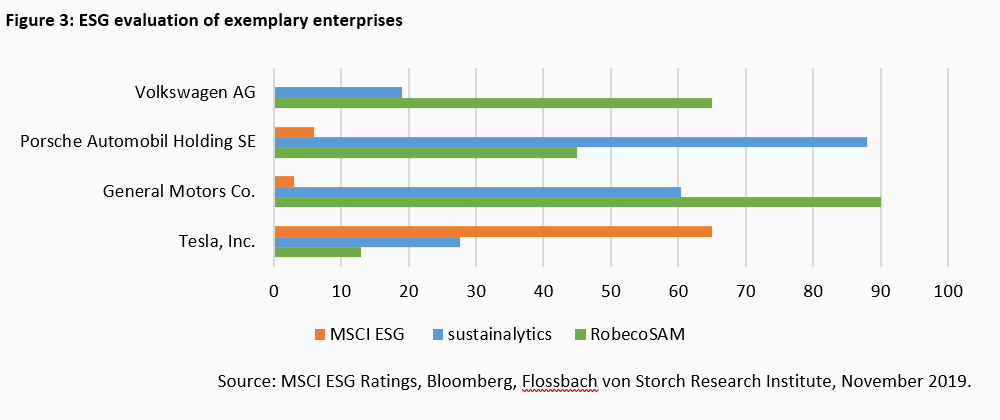

Figure 3 shows the ESG assessments of the different suppliers for selected enterprises from the automotive sector. In some cases there are significant differences between the respective assessments.10

While Volkswagen AG scored 0 points for the rating provider MSCI ESG and only about 19 points for Sustainalytics (with 100 points representing the best possible score), RobecoSAM evaluated Volkswagen's ESG performance with 65 points. Porsche Automobil Holding SE, on the other hand, scored 88 points in Sustainalytics, while RobecoSAM scored 45 points, significantly worse. The American manufacturers General Motors (GM) and Tesla are also rated very differently depending on the rating agency. For example, GM scored just 3 points for MSCI ESG, while the other two providers rewarded the sustainability efforts with 60 and 90 points respectively. Tesla, on the other hand, is rated above average by MSCI ESG with 65 points, while Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM are rated far below average with 28 and 13 points respectively. If one compares the corporations with the 100 highest ratings in each case, a total of 235 different names result. Only eleven groups are among the top 100 among all three rating providers.

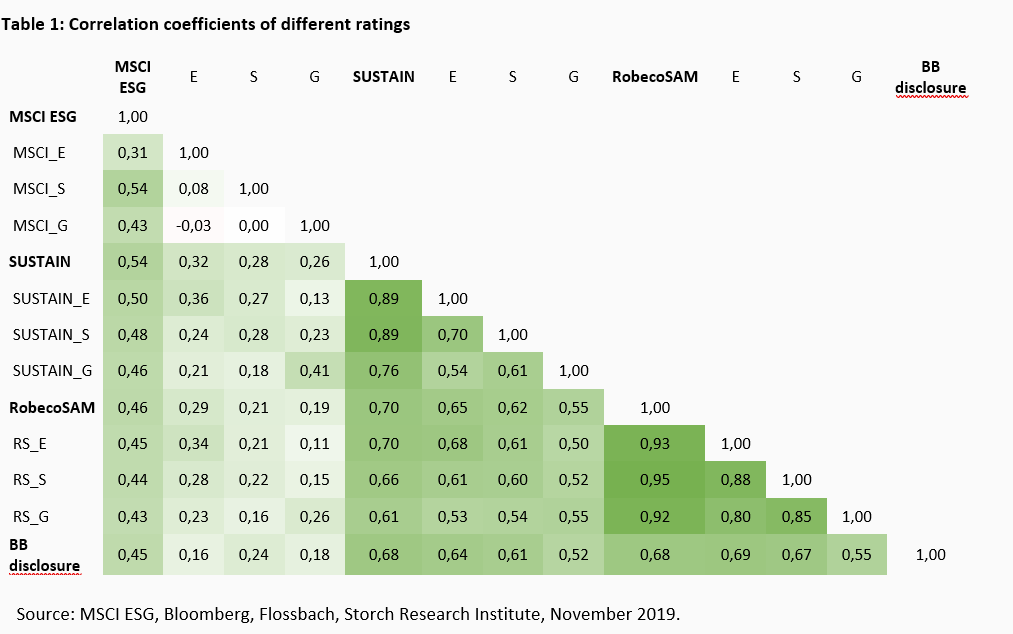

As Table 1 shows, the correlation between the ratings of the individual providers is clearly positive, but far from perfect, as the previous remarks have already suggested. The correlation coefficients between the MSCI ESG ratings and the Sustainalytics (abbreviated SUSTAIN) and RobecoSAM ratings are 0.54 and 0.46, respectively. There is a closer correlation between the ratings of the latter two providers. The correlation coefficient here is 0.70. It is interesting to note that the ratings for the individual dimensions in MSCI ESG are not correlated, i.e. a high score in the area of Environmental (abbreviated MSCI_E) does not correlate with high ratings in the area of Social (MSCI_S) or Governance (MSCI_G). Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM show clearly positive correlations. It is not possible to determine in detail what causes the significant differences in estimates. In addition to differences in the assessment of reviewed facts, methodological differences, for example in the weighting of the individual ESG dimensions and different information bases, are likely to make a significant contribution to explanation.

In order to estimate the effect of ESG reporting on rating results, the correlation matrix was supplemented by a disclosure score from the information service provider Bloomberg (BB disclosure). This essentially measures the scope of the report (see Appendix). Basically, larger and more profitable companies have better opportunities to strengthen their sustainability efforts and report on them. Due to the low degree of standardization and binding nature of ESG information, companies have incentives to overweight positive sustainability information.

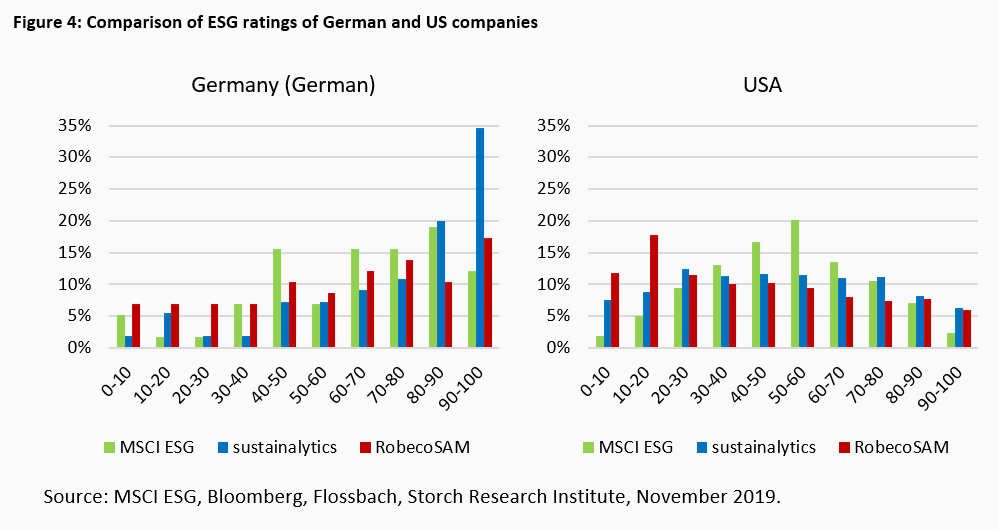

Table 1 shows a clearly positive correlation between the disclosure score and the rating results. The correlation coefficients lie between 0.45 and 0.68 depending on the provider. This shows that more comprehensive ESG reporting is accompanied by comparatively high scores. This is likely to explain why, against the background of the comparatively extensive EU CSR reporting obligations, German corporations perform significantly better in all three ratings than US companies (see Figure 4). While only about a quarter of German companies receive a rating of 50 points or worse and thus three quarters are above this score, 50% of US-american companies are below or above this score. As indicated, however, the higher valuations are not necessarily causally attributable to any "more sustainable" German companies. This requires causality analyses that validly measure the connection between a (however) defined sustainability and control the scope of the reporting.

With the rapid growth of the market for sustainable investments, the importance of corporate performance in the area of sustainability has increased significantly. As the subject is complex and assessment is complex and time-consuming, an increasing number of investors are using the services of specialised ESG rating providers. However, in the absence of a common understanding of the term "sustainability", it is not clear what such ESG ratings are intended to measure at all.

The present study shows that the assessments of individual ESG rating agencies sometimes differ significantly from one another. A responsible handling of the assessments is therefore appropriate. There is no doubt that such evaluations often offer valuable indications and food for thought. However an unreflected implementation of the judgments does not correspond to the claim of responsible investing.

MSCI ESG Ratings

A comprehensive description of the rating methodology is available at: https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/123a2b2b-1395-4aa2-a121-ea14de6d708a, last accessed: 07 November 2019.

RobecoSAM

Rank of total sustainability, converted from the score of total sustainability, based on the RobecoSAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment. The total sustainability score of a company is the sum of all question scores and ranges from 0 to 100. The total sustainability score is based on individual questions, which are summarised in criteria, which in turn are summarised in three dimensions - economic, ecological and social. The types and weights of the individual questions and criteria are adjusted for each sector-specific questionnaire to reflect the materiality of specific sustainability issues within each sector. The overall sustainability score can be defined as follows: Score of total sustainability = (number of question points received x weight of question x weight of criterion).

RobecoSAM is an investment specialist focusing exclusively on sustainable investing. Together with Standard & Poor's (S&P) Dow Jones Indices, RobecoSAM publishes the globally recognized Dow Jones Sustainability Indices. RobecoSAM Scores are based on the answers of the RobecoSAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment.

Source: Bloomberg, November 2019.

Sustainalytics

Total percentile rank assigned to the company based on its overall environmental, social and governance (ESG) score compared to its competitors. For the top 1% the percentile is 99%; for the bottom 1% the percentile is 1%. This is Sustainalytics most comprehensive percentile ranking. Aggregate ESG Performance encompasses the levels of willingness, openness and participation in the discussion existing in the company in all three ESG areas.

Sustainalytics provides comprehensive coverage of key global markets and flexible environmental, social and governance (ESG) research tools designed to be easily integrated into investment processes and systems.

Source: Bloomberg, November 2019.

Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score

Proprietary Bloomberg score based on the scope of a company's environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure. Companies that are not covered by the ESG Group have no score and show 'n.a.'. Companies that don't publish anything also show 'n.a.'. The score ranges from 0.1 for companies that disclose a minimum amount of ESG data to 100 for those that disclose each data point collected by Bloomberg. Each data point is weighted according to its importance, with data such as greenhouse gas emissions having a greater weight than other disclosures. The result (score) is also adapted to different branches of industry. Thus, each company is evaluated only on the basis of data relevant to the industrial sector in question. This score measures the amount of ESG data that a company publicly reports; it does not measure the company's performance for any given data point.

Source: Bloomberg, November 2019.

1 Special mandates and investment funds account for around two thirds of this volume.

2 The total of funds in Figure 1, right, differs from the total of sustainable investments in Figure 1, left, as the latter also includes customer deposits with specialist banks with a sustainability focus and sustainably managed own deposits of KfW and DekaBank. See FNG - Market Report Sustainable Investments 2019, available at: https://www.forum-ng.org/images/stories/Publikationen/fng-marktbericht_2019.pdf, last download: 15 November 2019.

3 For example, companies that fall under the definition of § 289b (1) HGB must report on environmental concerns (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption or air pollution), employee concerns, social concerns, respect for human rights and the fight against corruption or bribery. See § 289c (2) HGB. However, the "comply-or-explain" approach allows companies to de facto free themselves from the reporting obligation.

4 The auditor only has to check whether there is a so-called non-financial statement. An examination of the contents is not planned, however.

5 See Escrig-Olmedo et al. (2019), Rating the Raters: Evaluating how ESG Rating Agencies Integrate Sustainability Principles, in: Sustainability 2019, pp. 3ff. for a comprehensive analysis of the ESG rating market.

6 a.a.o., p. 10f.

7 There is no doubt that these variables are in turn influenced in the long term by social aspects or the type of company management. In this respect, these factors have always been an implicit component of classic ratings.

8 See Windolph (2011), Assessing Corporate Sustainability Through Ratings: Challenges and Their Causes, in: Journal of Environmental Sustainability, Vol. 1 (1), pp. 36-57 und Keller (2015), Chancen und Grenzen von ESG-Ratings, CMF Thesis Series No. 17 (2015), pp. 24ff.

9 Utz (2019), Corporate scandals and the reliability of ESG assessments: evidence from an international sample, in: Review of Management Science, Vol. 13 (2), S. 483-511.

10 In order to standardize the scaling, the scores of MSCI ESG Research were increased tenfold, so that they also range between 0 and 100 points.

16.08.2018 - Society & Finance

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.